Crown & Influence: Edmund Crouchback - The Loyal Brother Who Founded Lancaster

Edward I's younger brother built the foundations of the Lancastrian dynasty while remaining steadfastly loyal to the crown

In the turbulent world of medieval royal families, where brothers often became rivals and succession disputes led to civil wars, Edmund of Lancaster stands out as a rare example of fraternal loyalty. As younger brother to Edward I—one of England's most formidable kings—Edmund could easily have become a threat or a rebel. Instead, he served his brother faithfully for decades, commanded armies, governed territories, and founded the House of Lancaster that would eventually produce kings. His nickname "Crouchback" has sparked centuries of speculation, but Edmund's true significance lies not in physical characteristics but in his role as the loyal prince who built a powerful dynasty while never threatening his brother's throne.

The Second Son's Destiny

Edmund was born in January 1245, the second son of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. His elder brother, the future Edward I, was six years older and clearly destined for the throne. Edmund's role, like that of most younger royal sons, was to support his elder brother, provide military service, and marry strategically to build alliances—never to compete for power.

The meaning of Edmund's nickname "Crouchback" has been debated for centuries. Some claimed it meant hunchback, suggesting a physical deformity. Others argued it derived from "crossback," referring to crusader vows. Modern historians generally believe the nickname came later and may simply have distinguished this Edmund from the many other Edmunds in the royal family, or possibly referenced a slightly stooped posture that developed with age. Whatever its origin, the nickname has made Edmund more memorable than many medieval princes.

Edmund grew up during one of the most turbulent periods in English history. His father Henry III was a weak king who faced constant baronial opposition, culminating in the Second Barons' War (1264-67) led by Simon de Montfort. Young Edmund witnessed his father's capture at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, when he was only nineteen. He and his brother Edward were taken hostage by the rebel barons as surety for Henry's cooperation.

The experience must have been formative. Edmund saw firsthand how baronial overreach could threaten the monarchy and how crucial family loyalty was to royal survival. When Edward escaped captivity and began the military campaign that would destroy de Montfort's rebellion, Edmund supported him. At the Battle of Evesham in 1265, where de Montfort was killed and the rebellion crushed, Edmund fought alongside his brother.

The Sicilian Fiasco

Before the Barons' War, Edmund had briefly been caught up in one of his father's most disastrous schemes. In 1254, Pope Innocent IV offered the Kingdom of Sicily (actually southern Italy and Sicily) to Henry III for his second son. Henry, always ambitious and impractical, accepted on Edmund's behalf. Nine-year-old Edmund was now nominally King of Sicily, though he had never been there and would never go.

The Sicilian venture was a catastrophe. It required vast sums of money England didn't have to fight wars against the current Sicilian rulers. The English barons refused to fund this adventure, and the whole scheme collapsed, contributing to the political crisis that led to the Barons' War. Edmund was quietly relieved of his paper crown, ending his brief reign over a kingdom he never saw.

The Sicilian episode was embarrassing, but it wasn't Edmund's fault—he had been a child when his father accepted on his behalf. Still, it demonstrated the kinds of impractical schemes that plagued Henry III's reign and that Edward I would work to avoid once he became king.

The Lancastrian Foundation

Edmund's true significance began with his marriage and the estates that came with it. In 1267, after the Barons' War ended, Edmund married Aveline de Forz, daughter and heiress of the Earl of Aumale. She brought him significant estates, though the marriage was brief—Aveline died in 1274 without children.

Edmund's second marriage in 1276 was far more consequential. He married Blanche of Artois, widow of the King of Navarre and a member of the French royal family. Through Blanche, Edmund gained further estates and important Continental connections. More importantly, this marriage produced three sons who survived to adulthood: Thomas, Henry, and John.

But Edmund's real foundation of power came from his brother. In 1267, Edward I (then still prince) granted Edmund the honor, county, and castle of Lancaster, along with other estates. When Edward became king in 1272, he continued to grant Edmund lands and titles. In 1267, Edmund was created Earl of Lancaster, and over the following years, Edward granted him additional estates including Leicester.

These grants were extraordinarily generous, making Edmund one of the wealthiest and most powerful nobles in England. The Lancaster estates would pass to Edmund's descendants, eventually forming the basis of the Duchy of Lancaster that would become the richest noble holding in England and the foundation of the Lancastrian dynasty's power.

Why was Edward so generous to his younger brother? Partly, it was practical politics—a wealthy, loyal brother was a powerful supporter who would never threaten the throne. Partly, it was genuine affection—the brothers seem to have had a close relationship. And partly, it was compensation—Edmund was serving Edward loyally in military and administrative roles, and these estates provided both reward and the resources to continue that service.

The Soldier and Administrator

Edmund spent much of his career in military service to his brother. He fought in Wales during Edward's conquest campaigns, commanding armies and besieging castles. He served in Gascony, defending English territories in France against local rebels and French encroachment. He was appointed Lieutenant of Aquitaine, essentially governing England's French territories on Edward's behalf.

Edmund was a capable if not brilliant military commander. He won no spectacular victories like his nephew Edward II would temporarily achieve at Falkirk, but he provided steady, reliable leadership. His real value was administrative—he could govern territories, maintain order, and manage the complex logistics of medieval warfare and administration.

Edmund also served as a diplomat, negotiating with French kings and other rulers. His marriage connections to the French royal family and Navarre made him valuable in Continental diplomacy. He helped negotiate the treaty of 1279 between Edward and Philip III of France, temporarily settling disputes over Aquitaine.

In England, Edmund served on the royal council, advising his brother on matters of state. He witnessed charters, presided at parliaments when Edward was absent, and generally served as a reliable deputy for the king. He was trusted completely by Edward—there was never any hint of rivalry or ambition to challenge his brother's authority.

The Crusader

Like many nobles of his generation, Edmund took crusading vows. In 1271-72, he accompanied his brother Edward on crusade to the Holy Land. The crusade was small and ultimately unsuccessful, but Edmund distinguished himself through his participation.

Crusading was expensive and dangerous, but it was also how medieval nobles demonstrated piety and won prestige. Edmund's participation showed his commitment to the religious ideals of his age. Some have argued that "Crouchback" might reference this crusading service (cross-back), though this etymology is disputed.

Edmund's crusading may also have influenced his later patronage of religious houses. He founded several religious institutions, including a house of friars at Leicester, and was a generous patron of the Church. This religious devotion was typical of medieval nobility, but Edmund seems to have been genuinely pious rather than merely conventional in his faith.

The Loyal Brother's Death

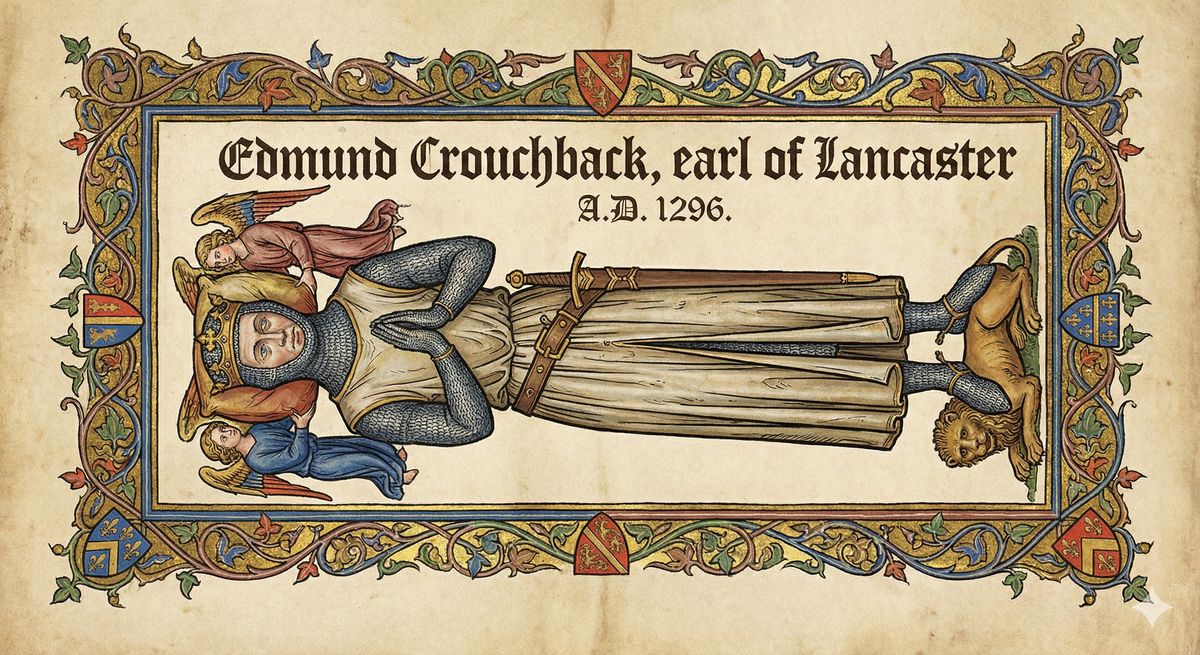

Edmund died in June 1296 at age fifty-one, possibly from illness contracted during military service in Gascony. He was buried at Westminster Abbey, a mark of his royal status and his brother's affection. Edward I erected an elaborate tomb for Edmund, demonstrating the importance he placed on his brother's memory and service.

Edmund's death came at a crucial time. Edward I was engaged in wars in Scotland, Wales, and France, and he had relied heavily on Edmund's support. Edmund's eldest son Thomas inherited the Lancaster estates and titles, but Thomas would prove very different from his father—ambitious, rebellious, and ultimately antagonistic to Edward II, Edmund's nephew. The loyalty that characterized Edmund's relationship with Edward I would not extend to the next generation.

The Lancastrian Foundation

Edmund Crouchback's historical significance lies primarily in what he founded rather than what he achieved personally. He was the first Earl of Lancaster, and the Lancaster estates he accumulated became the basis for one of medieval England's most powerful noble houses.

Edmund's descendants would shape English history profoundly. His son Thomas would lead baronial opposition to Edward II. His grandson Henry of Grosmont would become Duke of Lancaster and one of Edward III's greatest generals. His great-granddaughter Blanche would marry John of Gaunt, bringing the Lancaster estates into the royal family. John of Gaunt's son would become King Henry IV, beginning the Lancastrian dynasty that ruled England from 1399 to 1461.

In a very real sense, Edmund founded the dynasty that would eventually challenge and supplant the direct line of Edward I. The Lancaster estates he accumulated provided the wealth and power base that made the Lancastrian claim to the throne viable. The loyalty he showed to his brother would be ironically repaid by his descendants' rebellion against and deposition of Edward's descendants.

Edmund also demonstrated that younger royal sons could build powerful positions without threatening the throne. His loyal service to Edward I provided a model (if one rarely followed) for how princes could support rather than challenge their siblings. In an age when royal brothers often became rivals—one need only look at the conflicts between Henry III and his brother Richard of Cornwall, or the later tensions between various Plantagenet princes—Edmund's steadfast loyalty was remarkable.

Edmund was not a great warrior, a brilliant administrator, or a charismatic leader. He was competent rather than exceptional in most areas. But his importance lies in his role as foundation-builder and in his demonstration that loyalty could be rewarded and sustained. He built the Lancastrian power base while remaining faithful to the crown—a paradox that his descendants would resolve by taking the crown for themselves.

Edmund Crouchback remains a somewhat obscure figure, overshadowed by his more famous brother Edward I and by his more dramatic descendants. But his importance to English royal history is substantial. He founded the House of Lancaster, provided loyal service through decades of war and governance, and demonstrated that a prince could be both powerful and loyal. In the complex, often violent world of medieval royal families, Edmund's steadfast brotherhood with Edward I stands as a rare example of fraternal cooperation that benefited both brothers and, ultimately, the kingdom they served.